Summary

The history of Finland begins around 9,000 BC at the end of the last ice age. The Stone Age cultures were the Kunda, Comb Ceramic, Corded Ware, Kiukainen and Pöljä cultures. The Finnish Bronze Age started in about 1500 BC and the Iron Age started in 500 BC and lasted until 1300 AD. Finnish Iron Age cultures can be divided into Finnish real, Tavastian and Karelian cultures. The earliest written sources mentioning Finland appear from the 12th century, when the Catholic Church gained a foothold in southwestern Finland.

As a result of the Northern Crusades and the Swedish colonization of some Finnish coastal areas, most of the region became part of the Kingdom of Sweden and the realm of the Catholic Church from the 13th century onwards. After the Finnish War in 1809, the vast majority of the Finnish-speaking areas of Sweden were ceded to the Russian Empire (with the exception of areas in present-day northern Sweden where Meänkieli dialects of Finnish are spoken), making this area the became an autonomous Grand Duchy. from Finland. Lutheran religion dominated. Finnish nationalism emerged in the 19th century. It focused on Finnish cultural traditions, folklore and mythology, including music and – above all – the very distinctive language and lyrics associated with it. A product from this time was the Kalevala, one of the most important works of Finnish literature. The catastrophic Finnish famine of 1866-1868 was followed by relaxed economic regulations and extensive emigration.

Finland declared independence in 1917. A civil war between the Finnish Red Guards and the White Guards ensued a few months later, with the Whites gaining the upper hand in the spring of 1918. After internal affairs had stabilised, the mainly agricultural economy grew relatively quickly. Relations with the West, especially Sweden and Britain, were strong, but tensions with the Soviet Union persisted. During World War II, Finland fought the Soviet Union twice, first defending its independence in the Winter War and then invading the Soviet Union during the Continuation War. In the peace settlement, Finland eventually ceded much of Karelia and some other territories to the Soviet Union. Finland, however, remained an independent democracy in Northern Europe.

In the second half of its independence history, Finland has had a mixed economy. Since the economic boom after World War II in the 1970s, GDP per capita has been among the highest in the world. Finland’s expanded welfare state of 1970 and 1990 increased the number of employees and expenditure in the public sector and the tax burden on citizens. In 1992, Finland was simultaneously confronted with economic overheating and depressed Western, Russian and local markets. Finland joined the European Union in 1995 and replaced the Finnish markka with the euro in 2002. According to a 2016 poll, 61% of Finns preferred not to join NATO.

On 29-6-2022, NATO leaders took a historic decision to invite Finland and Sweden to join the alliance, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. On 4 April 2023, the last NATO members ratified Finland’s application to join the alliance, making Finland the 31st member.

Paleolithic – Mesolithic – Neolithic

Paleolithic

If confirmed, the oldest archaeological site in Finland would be the Wolf Cave in Kristinestad, in Ostrobothnia. The site is said to be the only pre-glacial (Neanderthal) site discovered so far in the Nordic countries and is about 125,000 years old.

Mesolithic

The last ice age in the area of present-day Finland ended c. 9000 BC. From that time, people migrated to the area of Finland from the south and southeast. Their culture represented a mixture of Kunda, Butovo and Veretje cultures. At the same time, Northern Finland was inhabited via the coast of Norway. The oldest confirmed evidence of post-glacial human settlement in Finland comes from the area of Ristola in Lahti and from Orimattila, from c. 8900 BC. Finland has been continuously inhabited since at least the end of the last ice age. The earliest post-glacial inhabitants of the present-day area of Finland were probably mainly seasonal hunter-gatherers. Among the finds is Antrea’s net, the oldest fishing net known to have been excavated (calibrated radiocarbon dating: c. 8300 BC).

Neolithic

By 5300 BC pottery was present in Finland. The earliest samples belong to the Comb Ceramic Cultures, known for their distinctive decorative patterns. This marks the beginning of the Neolithic period for Finland, although subsistence was still based on hunting and fishing. During the 5th millennium BC, extensive exchange networks existed in Finland and Northeastern Europe. For example, flint from Scandinavia and the Valdai Hills, amber from Scandinavia and the Baltic region, and slate from Scandinavia and Lake Onega found their way to Finnish archaeological sites, while asbestos and soapstone from Finland (for example, the area of Saimaa) were found. in other regions. Petroglyphs – apparently related to shamanistic and totemistic belief systems – have been found, especially in Eastern Finland, eg Astuvansalmi.

Between 3500 and 2000 BC, monumental stone fences popularly known as Giant’s Churches (Finnish: Jätinkirkko) were built in the Ostrobothnia region. The purpose of the attachments is unknown.

In recent years, an excavation at the Kierikki site north of Oulu on the River Ii (Ilijoki) has changed the picture of Finnish Neolithic Stone Age culture. The site was inhabited year-round and traded on a large scale. Kierikki culture is also seen as a subtype of Comb Ceramic culture. More of the site is excavated every year.

From 3200 BC, immigrants or a strong cultural influence from the south of the Gulf of Finland settled in southwestern Finland. This culture was part of the European Battle Ax cultures, which were often associated with the movement of the Indo-European speakers. The culture of the battle axe, or cord ceramic, appears to have practiced farming and ranching outside Finland, but the earliest confirmed traces of farming in Finland date from later, approximately to the 2nd millennium BC. Further inland, the societies retained their hunting and gathering lifestyle for the time being.

The cultures of the hatchet and comb ceramics eventually merged, giving rise to the Kiukainen culture that existed between 2300 BC and 1500 BC, and was essentially a tradition of comb ceramics with cord ceramic features.

Bronze Age – Iron Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age began some time after 1500 BC. The coastal areas of Finland were part of the Nordic Bronze Culture, while inland the influences came from the bronze cultures of northern and eastern Russia.

Iron Age

The Iron Age in Finland is believed to last from c. 500 BC to c. 1300 AD when known official and written records of Finland became more frequent due to the Swedish invasions as part of the Northern Crusades in the 13th century. Since the Finnish Iron Age lasted almost two millennia, it is further divided into six sub-periods:

- Pre-Roman period: 500 BC ch. – 1 sc. ch.

- Roman period: 1 AD ch. – 400 A.D. ch.

- Migration period: 400 AD. ch. – 575 A.D. ch.

- Merovingian period: 575 AD. ch. – 800 A.D. ch.

- Viking Age Period: 800 AD. ch. – 1025 A.D. ch.

- Crusade Period: 1033 AD. ch. – 1300 A.D. ch.

There are very few written records of Finland or its people in any language. Primary written sources are thus mostly of foreign origin, the most informative of which include Tacitus’ description of Fenni in his Germania, the sagas written down by Snorri Sturluson, as well as the 12th- and 13th-century ecclesiastical letters written for Finns. Numerous other sources from the Roman period contain brief mentions of ancient Finnish kings and place names, describing Finland as a kingdom and mentioning the culture of its people.

Currently, the oldest known Scandinavian documents mentioning a “land of the Finns” are two runestones: Söderby, Sweden, inscribed finlont, and Gotland, inscribed finlandi, from the 11th century. However, as the long continuum of the Finnish Iron Age into the historical medieval period of Europe suggests, the primary source of information of the era in Finland is based on archaeological finds and modern applications of scientific methods such as those of DNA analysis or computational linguistics.

Currently, the oldest known Scandinavian documents mentioning a “land of the Finns” are two runestones: Söderby, Sweden, inscribed finlont, and Gotland, inscribed finlandi, from the 11th century. However, as the long continuum of the Finnish Iron Age into the historical medieval period of Europe suggests, the primary source of information of the era in Finland is based on archaeological finds and modern applications of natural science methods such as those of DNA analysis or computational linguistics. .

Iron production during the Finnish Iron Age was taken over from neighboring cultures to the east, west and south around the same time as the first imported iron artifacts appear. This happened almost simultaneously in different parts of the country.

Pre-Roman, Roman, Migration & Merovingian Period

Pre-Roman period: 500 BC ch. – 1 sc. ch.

The pre-Roman period of the Finnish Iron Age is scarce in finds, but the known ones suggest that there were already cultural connections with other Baltic cultures. The archaeological finds of Pernaya and Savukoski prove this argument. Many of the residences of the era are the same as those of the Neolithic. Most of the iron from that time was produced on site.

Roman period: 1 AD ch. – 400 A.D. ch.

The Roman era brought with it an influx of imported iron (and other) artifacts such as Roman wine glasses and dippers, as well as various coins of the Empire. During this period (proto) Finnish culture stabilized in the coastal areas and larger cemeteries became commonplace. The wealth of the Finns rose to the level that the vast majority of gold treasures found in Finland date from this period.

Migration period: 400 AD. ch. – 575 A.D. ch.

The Migration Period saw the expansion of agricultural cultivation inland, especially in southern Botnia, and the growing influence of Germanic cultures, both in artifacts such as swords and other weapons and burial customs. Most iron and forging, however, was of domestic origin, probably marsh iron.

Merovingian period: 575 AD. ch. – 800 A.D. ch.

The Merovingian period in Finland gave rise to a distinctive craft culture of its own, visible in the original decorations of domestically produced weapons and jewellery. However, the best luxury weapons were imported from Western Europe. The very first Christian burials also date from the latter part of this time. In the burial results of Leväluhta, it was initially thought that the average height of a man was only 158 cm and that of a woman was 147 cm. but recent research has corrected these figures upwards and confirmed that the people buried in Leväluhta were of average height in Europe before that time.

Recent findings suggest that Finnish trade relations became more active as early as the 8th century, triggering an influx of silver into Finnish markets. The opening of the eastern route to Constantinople through the Finnish archipelago on the southern coastline brought Arab and Byzantine artifacts into the excavations of the time.

The earliest finds of imported iron knives and local ironwork appear in 500 BC. From about AD 50, there is evidence of a more intensive long-distance exchange of goods in the coast of Finland. Inhabitants exchanged their products, presumably mainly furs, for weapons and ornaments with the Balts and Scandinavians, as well as with the peoples along the traditional eastern trade routes. The existence of richly decorated tombs, usually with weapons, suggests that an elite existed mainly in the south and west of the country. Hill forts stretched across most of southern Finland in the late Iron and early Middle Ages. There is no generally accepted evidence of early state formations in Finland, and the suspected origin of Iron Age urbanization is disputed.

Middle Ages

Contact between Sweden and what is now Finland was considerable even in pre-Christian times; the Vikings were known to the Finns for their participation in both trade and plunder. There may be evidence of Viking settlement on the Finnish mainland. The Åland Islands probably had a Swedish settlement during the Viking period. However, some scholars argue that the archipelago was deserted in the 11th century. According to the archaeological findings, Christianity gained a foothold in Finland in the 11th century. According to the very few written documents that have survived, the church in Finland in the 12th century was still in its early development. Later medieval legends from the late 13th century describe Swedish attempts to conquer and Christianize Finland sometime in the mid-1150s.

In the early 13th century, Bishop Thomas became the first known bishop of Finland. There were several secular powers that wanted to bring the Finnish tribes under their rule. These were Sweden, Denmark, the Republic of Novgorod in northwestern Russia and probably the German Crusaders as well. Finns had their own leaders, but most likely no central authority. At that time, three cultural areas or tribes can be seen in Finland: Finns, Tavastians and Karelians. Russian chronicles indicate that there were several conflicts between Novgorod and the Finnic tribes from the 11th or 12th century to the early 13th century.

It was the Swedish regent, Birger Jarl, who is said to have established Swedish rule in Finland through the Second Swedish Crusade, usually dated to 1249. The Eric Chronicle, the only source to relate the “crusade,” describes it as targeting Tavastians. A papal letter from 1237 states that the Tavastians had reverted from Christianity to their ancient ethnic faith.

Novgorod took power in Karelia in 1278, the region inhabited by speakers of Eastern Finnish dialects. However, Sweden gained control of Western Karelia with the Third Swedish Crusade in 1293. From then on, West Karelians were seen as part of the Western cultural sphere, while East Karelians went culturally to Russia and Orthodoxy. Although the East Karelians remain linguistically and ethnically closely related to the Finns, they are generally considered a separate people. [30] Thus the northern part of the boundary between Catholic and Orthodox Christianity came to lie on the eastern border of what would become Finland with the Treaty of Nothenburg with Novgorod in 1323.

During the 13th century, Finland was integrated into medieval European civilization. The Dominican order arrived in Finland around 1249 and exerted great influence there. In the early 14th century, the first records of Finnish students at the Sorbonne appear. In the southwestern part of the country, an urban settlement arose in Turku. Turku was one of the largest cities in the Kingdom of Sweden, and its population was made up of German merchants and craftsmen. Otherwise, the degree of urbanization in medieval Finland was very low. Southern Finland and the long coastal zone of the Gulf of Bothnia had sparse settlements for agriculture, organized as parishes and castellanies. In the other parts of the country there was a small population of Sami hunters, fishermen and small-scale farmers. These were exploited by the Finnish and Karelian tax collectors. During the 12th and 13th centuries, large numbers of Swedish settlers moved to the southern and northwest coasts of Finland, to the Åland Islands and to the archipelago between Turku and the Åland Islands. In these regions, the Swedish language is widely spoken even today. Swedish also became the upper-class language in many other parts of Finland.

The name “Finland” originally meant only the southwestern province, which has been known as “Finland Proper” since the 18th century. The first known mention of Finland is in 11th century runestone Gs 13. The original Swedish term for the eastern part of the empire was Österlands (“Eastern Lands”), a plural, meaning the area of Finland Proper, Tavastia and Karelia. This was later replaced by the singular form Österland, which was in use between 1350–1470. In the 15th century, Finland began to be used synonymously with Österland. The concept of a Finnish “country” in the modern sense developed slowly from the 15th to the 18th.

The Diocese of Turku was established during the 13th century. Turku Cathedral was the center of the cult of Saint Henry of Uppsala and of course the cultural center of the diocese. The bishop had ecclesiastical authority over much of present-day Finland, and was usually the most powerful man there. Bishops were often Finns, while the commanders of castles were more often Scandinavian or German noblemen. In 1362 representatives from Finland were summoned to participate in the elections for the King of Sweden. As such, the year Finland was incorporated into the Kingdom of Sweden is often remembered. As in the Scandinavian part of the kingdom, the nobility or (lesser) nobility consisted of magnates and yeomen who could afford armaments for a man and a horse; these were concentrated in southern Finland.

The strong fortress of Viborg (Finnish: Viipuri, Russian: Vyborg) guarded Finland’s eastern border. Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg (Pähkinäsaari in Finnish) in 1323, but that did not last long. In 1348, Sweden’s King Magnus Eriksson conducted an unsuccessful crusade against Orthodox “heretics”, only managing to alienate his adherents and eventually lose his crown. The points of contention between Sweden and Novgorod were the northern coastline of the Gulf of Bothnia and the wilderness areas of Savo in eastern Finland. Novgorod regarded these as hunting and fishing grounds for his Karelian subjects and protested the slow infiltration of Catholic settlers from the West. Occasional raids and clashes between Swedes and Novgorodians took place during the late 14th and 15th centuries, but for most of the time there was an uneasy peace.

During the 1380s, a civil war in the Scandinavian part of Sweden also brought turmoil to Finland. The victor of this battle was Queen Margaret I of Denmark, who in 1389 brought under her rule the three Scandinavian kingdoms of Sweden, Denmark and Norway (the “Kalmar Union”). The next 130 years were marked by attempts by various Swedish factions to break out of the Union. Finland was sometimes involved in this struggle, but in general the 15th century seems to have been a relatively prosperous time[nodig citaat] , characterized by population growth and economic development. However, towards the end of the 15th century, the situation on the eastern frontier became tense. The Principality of Moscow conquered Novgorod and paved the way for a united Russia, and from 1495–1497 a war was fought between Sweden and Russia. The fortress town of Viborg withstood a Russian siege; according to a contemporary legend, it was saved by a miracle.

16th and 17th century

16th century

The Swedish Empire at its greatest. Most of present-day Finland was part of Sweden proper, rike, shown in dark green.

In 1521 the Kalmar Union collapsed and Gustav Vasa became the king of Sweden. During his reign, the Swedish Church was reformed. The state administration also underwent extensive reforms and development, giving it a much stronger grip on the lives of local communities – and the ability to collect higher taxes. Following the policy of the Reformation, Mikael Agricola, Bishop of Turku, published his translation of the New Testament into the Finnish language in 1551.

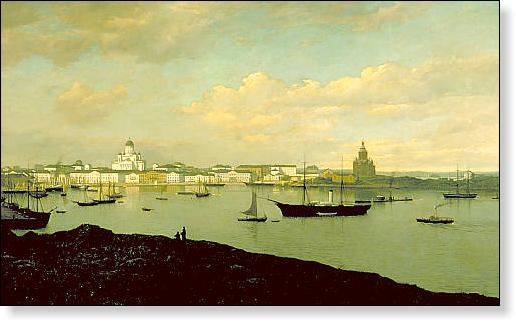

Helsinki was founded in 1550 by Gustav Vasa under the name Helsingfors, but remained little more than a fishing village for more than two centuries.

King Gustav Vasa died in 1560 and his crown was passed to his three sons in separate turns. King Erik XIV began an era of expansion when the Swedish crown took the city of Tallinn in Estonia under protection in 1561. This action contributed to the early stages of the Livonian War, a warlike era that lasted 160 years. In the first phase, Sweden fought for the rule of Estonia and Latvia against Denmark, Poland and Russia. The ordinary people of Finland suffered from drafts, high taxes and abuse by military personnel. This resulted in the Club War of 1596-1597, a desperate peasant uprising, which was brutally and bloodily suppressed. A peace treaty (the Treaty of Teusina) with Russia in 1595 moved Finland’s border further east and north, roughly where the modern border is.

An important part of Finland’s 16th-century history was the growth of the area inhabited by the peasant population. The crown encouraged farmers from the province of Savonia to settle in the vast wilderness areas of central Finland. This often forced the original Sami people to leave. Part of the inhabited wilderness was the traditional hunting and fishing area of Karelian hunters. This resulted in a bloody guerrilla war between the Finnish settlers and Karelians in some regions in the 1580s, especially in Ostrobothnia.

17th century

In 1611–1632, Sweden was ruled by King Gustavus Adolphus, whose military reforms transformed the Swedish army from a peasant militia into an efficient fighting machine, possibly the best in Europe. The conquest of Livonia was now complete and in the Treaty of Stolbova some territories were taken from internally divided Russia. In 1630, the Swedish (and Finnish) armies marched into Central Europe, as Sweden had decided to join the great battle between Protestant and Catholic troops in Germany known as the Thirty Years’ War. The Finnish light cavalry was known as the Hakkapeliitat.

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the Swedish Empire was one of the most powerful countries in Europe. During the war, several important reforms had been implemented in Finland:

1637-1640 and 1648-1654 Count Per Brahe acted as general governor of Finland. Many important reforms were carried out and many cities were founded. His term of office is generally considered very favorable for the development of Finland.

1640 Finland’s first university, the Academy of Åbo, was founded in Turku at the suggestion of Count Per Brahe by Queen Christina of Sweden.

1642 The entire Bible was published in Finnish.

However, the high taxes, ongoing wars and cold climate (the Little Ice Age) made Sweden’s imperial era rather bleak times for Finnish farmers. In 1655-1660, the Northern Wars were fought, bringing Finnish soldiers to the battlefields of Livonia, Poland and Denmark. In 1676 the political system of Sweden changed to an absolute monarchy.

In central and eastern Finland large quantities of tar were produced for export. European countries needed this material for the maintenance of their fleet. According to some theories, the spirit of early capitalism in the tar-producing province of Ostrobothnia may have been the reason for the witch-hunt wave that took place in this region at the end of the 17th century. The people developed more expectations and plans for the future, and when these were not realized, they quickly blamed the witches—according to a belief system the Lutheran church had imported from Germany.

The Empire had a colony in the New World in present-day Delaware-Pennsylvania between 1638 and 1655. At least half of the immigrants were of Finnish descent.

The 17th century was an era of very strict Lutheran orthodoxy. In 1608, the law of Moses was declared the law of the land alongside secular law. Every subject of the empire had to profess the Lutheran faith and church attendance was compulsory. Ecclesiastical punishments were widely used. The strict demands of Orthodoxy were revealed in the resignation of the Bishop of Turku, Johan Terserus, who wrote a catechism proclaimed heretical by the theologians of the Academy of Åbo in 1664. On the other hand, the Lutheran requirement of individual study of the Bible prompted the first attempts at large-scale teaching. The Church required each person to have a sufficient degree of literacy to read the basic texts of the Lutheran faith. Although the requirements could be met by memorizing the texts, reading skills also became known among the population.

In 1696-1699 Finland was decimated by a famine caused by the climate. A combination of early frosts, freezing temperatures that prevented grain from reaching Finnish ports, and a lackluster response from the Swedish government caused about a third of the population to die. Shortly afterwards, a new war began that determined the fate of Finland (the Great Northern War of 1700-1721).

18th century

Finland was depopulated by this time, with a population in 1749 of 427,000. With peace, however, the population grew rapidly, doubling before 1800. 90% of the population was typically classified as “farmers”, most of which were taxed freely. Society was divided into four estates: peasants (freely taxed yeomen), the clergy, nobility and citizens. A minority, mainly cottagers, were stateless and had no political representation. Forty-five percent of the male population had the right to vote with full political representation in the legislature — although clergy, nobles and townspeople had their own chambers of parliament, increasing their political influence and excluding the peasantry in foreign policy matters.

The mid-18th century was a relatively good time, partly because life was calmer now. However, during Lesser Wrath (1741–1742), Finland was reoccupied by the Russians after the government, during a period of Hat party dominance, failed to retake the lost provinces. Instead, the result of the Treaty of Åbo was to move the Russian border further west. During this time, Russian propaganda pointed to the possibility of creating a separate Finnish kingdom.

The Battle of Svensksund was a naval battle fought on 9-10 July 1790 in the Gulf of Finland outside the present-day city of Kotka.

Both the emerging Russian Empire and pre-revolutionary France aspired to Sweden as a customer state. Parliamentarians and others with influence were prone to take bribes, which they did their best to get.

The integrity and credibility of the political system declined, and in 1771 the young and charismatic King Gustav III staged a coup d’état, abolished parliamentarism and restored royal power in Sweden – more or less with the support of parliament. In 1788 he started another war against Russia. Despite a few victorious battles, the war was fruitless and only managed to disrupt Finland’s economic life. The popularity of King Gustav III significantly declined. During the war, a group of officers made the famous Anjala statement and demanded peace negotiations and the convening of the Riksdag (parliament). An interesting sideline of this process was the conspiracy of some Finnish officers, who tried to create an independent Finnish state with Russian support. After an initial shock, Gustav III crushed this opposition. In 1789, Sweden’s new constitution further strengthened the royal power and also improved the status of the peasantry. However, the ongoing war had to be ended without conquests – and many Swedes now viewed the king as a tyrant.

With the interruption of the war of Gustav III (1788–1790), the last decades of the 18th century were an era of development in Finland. Even everyday life changed new things, such as the start of potato cultivation after the 1750s. New scientific and technical inventions were seen. The first hot air balloon in Finland (and in the entire Swedish kingdom) was made in Oulu (Uleåborg) in 1784, just a year after it was invented in France. Trade increased and farmers became more prosperous and self-confident. The climate of the Age of Enlightenment of wider debate in society on issues of politics, religion and morals would over time emphasize the problem that the vast majority of Finns spoke only Finnish, but the cascade of newspapers, call notes and political pamphlets almost exclusively in Swedish – if not in French.

The two Russian occupations had been hard and were not soon forgotten. These professions were the seed of a sense of separateness and otherness, which in a small circle of scholars and intellectuals at the university in Turku developed a sense of a distinct Finnish identity that represented the eastern part of the empire. The radiant influence of the Russian imperial capital, St. Petersburg, was also much stronger in southern Finland than in other parts of Sweden, and contacts across the new frontier spread the greatest fears for the fate of the educated and merchant classes under a Russian regime. By the early 1800s, the Swedish-speaking classes of officers, clergy, and civil servants were mentally well prepared for a shift from allegiance to the strong Russian Empire.

King Gustav III was assassinated in 1792, and his son Gustav IV Adolf took over the crown after a period of regency. The new king was not a particularly talented ruler; at least not talented enough to lead his kingdom through the perilous era of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

Meanwhile, the Finnish territories belonging to Russia after the peace treaties in 1721 and 1743 (excluding Ingria), called ‘Old Finland’, were initially governed by the old Swedish laws (a not uncommon practice in the expanding Russian Empire in the 18th century) . Gradually, however, the rulers of Russia bestowed large estates on their non-Finnish favorites, ignoring the traditional land tenure and peasant freedom laws of ancient Finland. There were even cases when the nobles corporally punished peasants, for example by flogging. The general situation caused a decline in the economy and morale in old Finland, which had deteriorated since 1797 when the area was forced to send men to the Imperial army. The construction of military installations in the area brought thousands of non-Finnish people to the region. In 1812, after the Russian conquest of Finland, ‘Old Finland’ was rejoined the rest of the country, but the question of land tenure remained a serious problem until the 1870s.

Russian Grand Duchy, Independence & Civil War & Interwar period

Russian Grand Duchy

During the Finnish War between Sweden and Russia, Finland was again conquered by the armies of Tsar Alexander I. The four estates of occupied Finland were gathered together at the Diet of Porvoo on March 29, 1809, to swear allegiance to Alexander I of Russia. After the Swedish defeat in the war and the signing of the Treaty of Fredrikshamn on September 17, 1809, Finland remained a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire until the end of 1917, with the Tsar as Grand Duke.

Russia granted Karelia (“Old Finland”) to the Grand Duchy in 1812. During the years of Russian rule, the degree of autonomy varied. Periods of censorship and political persecution took place, especially in the last two decades of Russian control, but the Finnish peasants remained free (unlike the Russian serfs) as the old Swedish law remained in force (including the relevant parts of the constitution by Gustav III from 1772).

The old four-chamber diet was reactivated in the 1860s and passed additional new legislation governing internal affairs. In addition, the Finns remained free from obligations associated with the empire, such as the duty to serve in tsarist armies, and enjoyed certain rights that citizens from other parts of the empire did not have.

Independence and Civil War

In the wake of the February Revolution in Russia, Finland received a new Senate and coalition cabinet with the same power distribution as the Finnish parliament. On the basis of the general election in 1916, the Social Democrats had a small majority and the Social Democrat Oskari Tokoi became Prime Minister.

The new Senate was willing to cooperate with the Provisional Government of Russia, but no agreement was reached. Finland considered the personal union with Russia over after the Tsar’s dethronement – although the Finns had de facto recognized the Provisional Government as the Tsar’s successor by accepting its authority to appoint a new governor-general and senate. They expected the Tsar’s authority to be transferred to the Finnish parliament, which the provisional government refused, suggesting instead that the issue be resolved by the Russian Constituent Assembly.

To the Finnish Social Democrats, the bourgeoisie seemed to be an obstacle on the road to Finland’s independence and to the power of the proletariat. The non-socialists in the Tokoi Senate, however, were more confident. They, and most non-socialists in parliament, rejected the Social Democrats’ proposal on parliamentarism (the so-called “power law”) as too far-reaching and provocative. The law limited Russia’s influence on Finnish domestic affairs, but did not affect the Russian government’s power in defense and foreign affairs. However, for the Russian Provisional Government this was far too radical and beyond the authority of the Parliament, so the Provisional Government dissolved the Parliament.

The minority of parliament and of the senate were satisfied. New elections promised them a chance to win a majority, which they believed would increase the chances of reaching an agreement with Russia. The non-socialists were also inclined to cooperate with the Russian Provisional Government because they feared that the power of the Social Democrats would increase, leading to radical reforms, such as equal voting rights in municipal elections or a land reform. The majority had the completely opposite opinion. They did not accept the Provisional Government’s right to dissolve parliament.

The Social Democrats clung to the power law and opposed the promulgation of the decree to dissolve parliament, while the non-socialists voted in favor of it. The disagreement over the power law led to the Social Democrats leaving the Senate. When parliament reconvened after the summer recess in August 1917, only the factions that supported the power law were present. Russian troops took possession of the chamber, the parliament was dissolved and new elections were held. The result was a (small) non-socialist majority and a purely non-socialist senate. The suppression of the Power Act and the cooperation between Finnish non-socialists and Russia caused great bitterness among the socialists, and had resulted in dozens of politically motivated attacks and murders.

The October Revolution of 1917 turned Finnish politics upside down. Now the new non-socialist majority in Parliament longed for total independence, and the socialists gradually came to see Soviet Russia as an example to follow. On November 15, 1917, the Bolsheviks declared a universal right of self-determination “for the peoples of Russia”, including the right to complete secession. On the same day, the Finnish parliament issued a statement temporarily taking power in Finland.

Concerned about developments in Russia and Finland, the non-socialist senate proposed that parliament declare Finland’s independence, which was voted on by parliament on December 6, 1917. On December 18, the Soviet government issued a decree recognizing Finland’s independence, and on December 22 it was approved by the Supreme Executive Body of the Soviet Union (VTsIK). Germany and the Scandinavian countries followed without delay.

Civil war

Finland was bitterly divided along social lines after 1917. The whites consisted of the Swedish-speaking middle and upper classes and the peasants and peasants who dominated the northern two-thirds of the country. They had a conservative outlook and rejected socialism. The Socialist-Communist Reds consisted of the Finnish-speaking urban workers and the landless rural dwellers. They had a radical view and rejected capitalism.

From January to May 1918, Finland experienced the short but bitter Finnish Civil War. On the one hand, there were the “white” vigilantes, who fought for the anti-socialists. On the other side were the Red Guard, made up of laborers and tenant farmers. The latter proclaimed a Finnish Workers’ Socialist Republic. The First World War was still going on and the defeat of the Red Guards was achieved with support from the German Empire, while Sweden remained neutral and Russia withdrew its troops. The Reds lost the war and the white farmers rose to political leadership in the 1920s-1930s. About 37,000 men died, most of them in prison camps ravaged by the flu and other illnesses.

Finland in the interwar period

After the civil war, the parliament controlled by the whites voted to establish a constitutional monarchy that would be called the Kingdom of Finland, with a German prince as king. However, Germany’s defeat in November 1918 made the plan impossible and Finland became a republic instead, with Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg elected as its first president in 1919. Despite the bitter civil war and repeated threats from fascist movements, Finland became and remained a capitalist democracy. under the rule of law. By contrast, under similar circumstances but without civil war, nearby Estonia started out as a democracy and was turned into a dictatorship in 1934.

Finland in World War II

Finland in World War II

During World War II, Finland fought two wars against the Soviet Union: the Winter War of 1939-1940, resulting in the loss of the Finnish Karelia, and the Continuation War of 1941-1944 (with significant support from Nazi Germany resulting in a rapid invasion of from adjacent areas of the Soviet Union), ultimately leading to the loss of Finland’s only ice-free winter port, Petsamo. The War of Continuation, in accordance with the terms of the armistice, was immediately followed by the Lapland War of 1944-1945, when Finland fought the Germans to force them to withdraw from Northern Finland to Norway (then under German occupation). Finland was not occupied; his army of more than 600,000 soldiers saw only 3,500 prisoners of war. About 96,000 Finns were killed, or 2.5% of a population of 3.8 million; civilian casualties were less than 2,500.

In August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, transferring Finland and the Baltic states to the Soviet “sphere of influence”. After the invasion of Poland, the Soviet Union sent ultimatums to the Baltic states, demanding military bases on their territory. The Baltic states accepted Soviet demands and lost their independence in the summer of 1940.

In October 1939, the Soviet Union sent the same kind of request to Finland, but the Finns refused to give land areas or military bases for the use of the Red Army. This caused the Soviet Union to launch a military invasion against Finland on November 30, 1939. Soviet leaders predicted that Finland would be conquered within a few weeks. Although the Red Army had enormous superiority in men, tanks, guns and aircraft, the Finns were able to defend their country for about 3.5 months and still successfully avoid an invasion.

The Winter War ended on March 13, 1940 with the peace treaty of Moscow, in which Finland lost the Karelian Isthmus to the Soviet Union. The Winter War meant a great loss of prestige for the Soviet Union and was expelled from the League of Nations because of the illegal attack. Finland received a lot of international goodwill and material aid from many countries during the war.

After the Winter War, the Finnish army was exhausted and needed recovery and support as soon as possible. The British refused to help, but in the fall of 1940, Nazi Germany offered Finland arms deals if the Finnish government would allow German troops to travel through Finland into occupied Norway. Finland accepted, arms deals were made, and military cooperation began in December 1940.

Finland’s support and coordination with Nazi Germany began in the winter of 1940-1941 and made other countries considerably less sympathetic to the Finnish cause; especially since the Continuation War led to a Finnish invasion of the Soviet Union, intended not only to recapture lost territory, but also to respond to the irredentist sense of a Greater Finland by including Eastern Karelia, whose inhabitants are culturally related were to the Finnish people, though Orthodox by religion. By this invasion, Britain had declared war on Finland on December 6, 1941.

Finland managed to defend its democracy, unlike most other countries within the Soviet sphere of influence, and suffered relatively limited losses in terms of civilian lives and property. However, it was punished more severely than other German co-warring parties and allies, as it had to pay large reparations and resettle one-eighth of its population after losing one-eighth of its territory, including one of its industrial core areas and the second-largest largest city of Viipuri. After the war, the Soviet government settled these acquired territories with people from many different regions of the USSR, for example, from Ukraine.

The Finnish government did not participate in the systematic murder of Jews, although the country remained a “co-belligerent”, de facto ally of Germany until 1944. A total of eight German-Jewish refugees were handed over to the German authorities. At the Tehran Conference of 1942, Allied leaders agreed that Finland was waging a separate war against the Soviet Union, and that it was in no way hostile to its Western allies. The Soviet Union was the only allied country against which Finland had conducted military operations. Unlike all other Axis countries, Finland was a parliamentary democracy during the period 1939-1945.

The commander of the Finnish Defense Forces during the Winter War and the Continuation War, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim , became the President of Finland after the war.

Finland entered into a separate peace contract with the Soviet Union on September 19, 1944, and was the only bordering USSR country in Europe (besides Norway, which only got its own border with the Soviet Union after the war) to retain its independence after the war. the war.

During and between the wars, about 80,000 Finnish war children were evacuated abroad: 5% went to Norway, 10% to Denmark and the rest to Sweden. Most children were returned in 1948, but 15–20% remained abroad.

The Moscow Armistice was signed on September 19, 1944 between Finland on the one hand and the Soviet Union and Great Britain on the other, ending the war of continuation. The armistice forced Finland to expel German troops from its territory, leading to the 1944-1945 Lapphund War.

In 1947, Finland reluctantly refused Marshall Aid in order to maintain good relations with the Soviets and ensure Finnish autonomy. Nevertheless, the United States has been sending covert development aid and financial aid to the non-Communist SDP (Social Democratic Party). By establishing trade with the Western powers, such as Great Britain, and making reparations to the Soviet Union, Finland transformed from a primarily agricultural economy to an industrialized economy. After the reparations were paid off, Finland continued to trade with the Soviet Union through bilateral trade.

Finland’s role in World War II was strange in many ways. First, the Soviet Union attempted to invade Finland in 1939–1940. But even with an enormous superiority in military strength, the Soviet Union was unable to conquer Finland. At the end of 1940, the German-Finnish cooperation began; it took on a form that was unique compared to its relations with the Axis. Finland signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, which made Finland an ally with Germany in the war against the Soviet Union. However, unlike all other Axis states, Finland has never signed the Tripartite Pact and thus Finland has never been an Axis nation de jure.

Memorials

Although Finland lost ground in both wars with the Soviets, the memory of these wars was sharply etched in the national consciousness. Despite its military defeats, Finland celebrates these wars as a victory for the Finnish national spirit, which survived against all odds and allowed Finland to maintain its independence. Many groups of Finns are commemorated today, including not only fallen soldiers and veterans, but also orphans, evacuees from Karelia, the children evacuated to Sweden, women who worked at home or in factories during the war, and the veterans of the women’s defense unit Lotta Svärd. (ed.: this Lotta Svärd has a great resemblance to the Nazi swastika, but has nothing to do with it)

Some of these groups could not be properly commemorated until long after the end of the war in order to maintain good relations with the Soviet Union. However, after a long political campaign, supported by survivors of what the Finns call the Partisan War, the Finnish parliament passed legislation establishing compensation for the war victims.

1945 to present

1945 to present

Finland maintained a democratic constitution and a free economy during the Cold War. Treaties signed with the Soviet Union in 1947 and 1948 contain obligations and restrictions for Finland, as well as territorial concessions. The Paris Peace Treaty (1947) limited the size and nature of the Finnish armed forces. Weapons were to be solely defensive. A deepening of post-war tensions led to the 1948 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance with the Soviet Union. The latter in particular formed the basis of Finnish-Soviet relations in the post-war period. Under the terms of the treaty, Finland was required to consult with the Soviets and perhaps accept their assistance if an attack from Germany or countries allied with Germany seems likely. The treaty required consultations between the two countries, but it had no mechanism for automatic Soviet intervention in times of crisis. Both treaties have been withdrawn by Finland since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, while the borders remained untouched. While the Soviet Union’s neighbor at times resulted in overcautious foreign policy concerns (“Finlandization”), Finland developed closer co-operation with the other Nordic countries and declared itself neutral in superpower politics.

Finland’s post-war president, Juho Kusti Paasikivi, a leading conservative politician, recognized that an essential element of Finnish foreign policy should be a credible guarantee to the Soviet Union that it will not fear attacks from or through Finnish territory. Since a policy of neutrality was a political part of this guarantee, Finland would not unite with anyone. Another aspect of the guarantee was that the Finnish defenses had to be strong enough to defend the nation’s territory. This policy remained at the heart of Finland’s foreign relations throughout the remainder of the Cold War.

In 1952, Finland and the Nordic Council countries entered into a Passport Union, which allowed their citizens to cross borders without a passport and soon also apply for jobs and claim social benefits in the other countries. Many from Finland took this opportunity to secure better-paying jobs in Sweden in the 1950s and 1960s and dominated the first wave of post-war labor immigrants in Sweden. Although Finnish wages and living standards could not compete with wealthy Sweden until the 1970s, the Finnish economy rose remarkably from the ashes of World War II, resulting in the building of another Scandinavian-style welfare state.

Despite the passport union with Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland, Finland was not able to join the Nordic Council until 1955, because the Soviet Union feared that Finland would become too close to the West. At the time, the Soviet Union saw the Nordic Council as part of NATO, of which Denmark, Norway and Iceland were members. That same year, Finland joined the United Nations, although it had already been associated with a number of specialized UN agencies. The first Finnish ambassador to the UN was GA Gripenberg (1956-1959), followed by Ralph Enckell (1959-1965), Max Jakobson (1965-1972), Aarno Karhilo (1972-1977), Ilkka Pastinen (1977-1983), Keijo Korhonen (1983-1988), Klaus Törnudd (1988-1991), Wilhelm Breitenstein (1991–1998) and Marjatta Rasi (1998–2005). In 1972, Max Jakobson was a candidate for UN Secretary General. In another notable event in 1955, the Soviet Union decided to return the Porkkala Peninsula to Finland, which had been leased to the Soviet Union as a military base for 50 years in 1948, a situation that somewhat endangered Finnish sovereignty and neutrality. .

Finland, officially neutral, was in the gray zone between the western countries and the Soviet Union. The “YYA Treaty” (Finnish-Soviet Pact of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance) gave the Soviet Union some influence over Finnish domestic politics. However, Finland retained capitalism unlike most of the other countries bordering the Soviet Union. Property rights were strong. While nationalization committees were established in France and the UK, Finland avoided nationalizations. After failed experiments with protectionism in the 1950s, Finland eased restrictions and committed to a series of international free trade agreements: first associate membership in the European Free Trade Association in 1961, full membership in 1986 and also an agreement with the European Community in 1973. Local education markets expanded and an increasing number of Finns also went abroad to study in the United States or Western Europe, bringing back advanced skills. There was a fairly common but pragmatic credit and investment cooperation by the state and business, although it was viewed with suspicion. Support for capitalism was widespread. The savings rate hovered among the highest in the world until the 1980s, at around 8%. In the early 1970s, Finnish GDP per capita reached the level of Japan and the UK. Finland’s economic development shares many aspects with the export-led Asian countries.

Building on its status as a Western democratic country with friendly ties to the Soviet Union, Finland worked to ease the political and military tensions of the Cold War. Finland has been pushing for the creation of a Nordic Nuclear Weapon Free Zone (Nordic NWFZ) since the 1960s and hosted the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) in 1972-1973, which culminated in the signing of the Helsinki Accords in 1975 and led to the establishment of the OSCE.

The 1970s were characterized by rapidly successive cabinets of varying composition (13 governments in 10 years). All governments faced large trade deficits and unemployment.

Kekkonen , elected president in 1956, held a virtually unassailable position for years. After he was re-elected in 1962 and 1968, his term of office was automatically extended by four years after 1974 by an exception law. In 1978, the 77-year-old president was re-elected without much struggle, as all major parties supported his candidacy. On October 27, 1981, Kekkonen resigned for health reasons. He was succeeded by Prime Minister Koivisto.

He resolved the Finnish-Soviet-Russian differences and succeeded in further developing Finland’s commercial interests in Western Europe. In March 1992 Finland applied for EC membership. Earlier, on Jan. 1992, Finland concluded a friendship treaty with Russia. This treaty was a revised version of the 1948 treaty between Finland and the Soviet Union.

After a very deep recession, which the country had entered after 1990, the economic recovery continued in 1994. The rapprochement with the West remained a factor in Finnish politics, leading to EU membership in January 1995. In October 1996, the government decided to integrate the Finnish mark into the European Monetary System (EMS).

In February 2000, Finnish Foreign Minister Tarja Halonen won the Finnish presidential election. She became the first female head of state. In 2006 President Tarja Halonen is still very popular among the population and is re-elected for a second term. In April 2011, the centre-right National Coalition Party becomes the largest in the parliamentary elections. In June, Jyrki Katainen forms a new government that includes the far right new Finns. In February 2012, Sauli Niinistö becomes the first conservative president since 1956.

In October 2016, Finland signed an agreement with the US on enhanced military cooperation amid growing unrest over Russia’s actions towards the Baltic states. In December 2017, Finland will celebrate 100 years of independence. Niinisto won a second term as president in the 2018 election. Social Democrat Sanna Marin took over as prime minister of a center-left coalition in 2019 after her predecessor Antti Rinne resigned over his handling of a postal strike. Rinne, the leader of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), had come to power in June 2019 after defeating the center-right government. Marin was elected prime minister on December 8, 2019. At 35, she is the fourth youngest serving head of state in the world, the youngest female head of state and Finland’s youngest ever prime minister.

On 30-6-2022, NATO leaders took a historic decision to invite Finland and Sweden to become members of the alliance.

Jens Stoltenberg, the secretary general of NATO, said in a press conference that the agreement concluded between Turkey, Finland and Sweden paved the way for the decision to invite both Nordic countries to NATO.

From left during the signing of the agreement between Turkey, Finland and Sweden in Madrid, Spain, on June 28, 2022: Pekka Haavisto, the minister of foreign affairs of Finland, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, the minister of foreign affairs of Turkey, Jens Stoltenberg, the secretary general of NATO, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Türkey, President Sauli Niinistö of Finland and Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson of Sweden and Ann Linde, the minister of foreign affairs of Sweden.

On 24 February 2022, the Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered the Russian Armed Forces to begin the invasion of Ukraine. On 25 February, a Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson threatened Finland and Sweden with “military and political consequences” if they attempted to join NATO, which neither were actively seeking. After the invasion public support for membership rose significantly.

On 4 April 2023, the last NATO members ratified Finland’s application to join the alliance, making Finland the 31st member.

Petteri Orpo

In April 2023 Finnish parliamentary elections approached and the support for the ruling coalition and its policies waned.

The result of the elections was that no party had enough of a presence in the new Eduskunta to form a majority government, but, as the first-place finisher, the NCP (and the leader Petteri Orpo) was given the first opportunity to put together a ruling coalition. In June 2023 Orpo became prime minister at the head of a coalition government that included the NCP, the Christian Democrats, the Swedish People’s Party, and the Finns.

Alexander Stubb

Stubb elected Finland’s 13th president. Ruling Kansallinen Kokoomus (National Coalition Party-NCP) candidate Alexander Stubb has been elected Finland’s 13th president. Stubb, a former prime minister, narrowly defeated Vihreä Liitto (Green Party) leader Pekka Haavisto, who participated as an electoral association candidate in the second round of voting held on 11 February 2024. The president’s term begins on 1 March 2024.

Sources:

WiKiPedia, infofinland.fi, britannica.com, discoveringfinland.com,landenweb.nl, finland.fi