Midnight Sun

Like many celebrations in the Scandinavian countries, Juhannus or Midsummer with the Midnight Sun has its roots in a pagan tradition, which in this case was a devotion to Ukko -the God of weather/thunder- when it first began, hundreds of years ago. This was done to appease the God, bring good harvests and fertility to all those whose livelihood depended on agriculture, for the coming year.

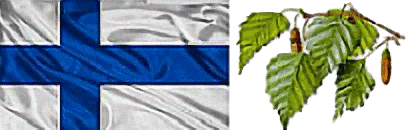

This holiday – an official holiday and flag day in Finland – has many different names depending on the country that celebrates it, but in the land of a thousand lakes it is called Juhannus.

However, this is not only a Finnish festival and Midsummer is also a big celebration in all Scandinavian countries, in Estonia and other Baltic states, Belarus, Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, Germany, Netherlands, and also observed by the Roman Catholic Church , Lutheran Churches, Anglican Communities and Neo-Pagans.

They may all have different names for it, but they all commemorate this holiday and its significance, which symbolizes the beginning of the astronomical summer (the beginning of the solstice), the ancient mid-summer, and the birth of John the Baptist.

This is where the name Juhannus actually comes from. In 1316, in an attempt to convert pagans to Christianity and to confuse the image of the God Ukko with that of a Christian saint, the Roman Catholic Church decided to attribute the date to the birth of John the Baptist, whose name was translated to John, who in time turned into Juhannus, thus becoming the name by which the day off is best known today.

A mix of pagan and Christian traditions

Today, because of all this, the festival is a mixed celebration of pagan and Christian traditions, when people light a bonfire or cast playful magic spells — like single girls collecting seven different wildflowers to later put under their pillows so that they can to see in their dreams who their future husbands will be.

Juhannus used to be celebrated every 24th June, but since 1955 it has always been celebrated on a Saturday, between 20th June and 26th June, with Midsummer Eve on every Friday before.

Traditionally in Finland the celebrations are held in nature because when Juhannus started it was believed that nature possessed special powers and magic and that is where spells would be more effective.

This is why to this day large bonfires (kokko) are lit, the midsummer pole is raised (usually in the Swedish-speaking areas), feast on various types of sausages (makkaras) and other grilled meats, fish, fern , singing, dancing, playing, drinking a lot, going to festivals and of course the sauna, all done in woods by a lake or the sea.

It is also traditional for Finns to place birch tree branches (koivu) on both sides of the doors and gates to welcome visitors and to go to their lake cottage (möki) – away from the bustle of the city – to celebrate these celebrations. to hold, relax and swim in the lake under the midnight sun. For this reason, it is common for the big cities to look empty and empty, as most Finns and many foreigners are away in their summer cottages, whether privately owned or rented.

Fire, a purifying power

The bonfires in particular play a special and vital role during this holiday because in ancient times fire was used in almost all cultures in Europe and people considered fire as a purifying and powerful force that brought good luck.

Although initially the bonfires were only common in Eastern Finland, over time this tradition spread all over the country. The first and oldest written record of midsummer fires dates back to 1645 in Turku.

When it comes to the Christian religious aspect of Juhannus, the celebrations include processions, baptisms, worship services, confirmations and church weddings, which increase in number significantly at this time of year.

But regardless of one’s personal religious affiliation or nationality, if they live in Finland and want to enjoy this holiday -and if they don’t have a Möki, don’t have a chance to rent one or leave the big city- there are still other places where Juhannus can be celebrated. Virtually every Finnish city has its own midsummer events planned and in the Helsinki area the most common and sought after venues are the island/open air museum of Seurasaari, where a traditional type of celebration takes place, and in the city center.